Samantha Modder’s large-scale drawings on paper intentionally take up space and are unapologetically themselves. The artist initiated the drawings using patterned fabric, which ultimately inspired the resulting characters. While the works themselves are bold in scale, they act to invite the viewer to participate in private moments in their lives. Inspired by Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken word piece of the same name from the 1970s, The revolution will not be televised urges the viewer to take action — providing a sense of urgency and courage. The work delivers Scott-Heron and Modder’s collective message: you cannot stay at home and passively join change, you have to get up and be involved. Below the facial hair is a self-portrait of Modder, reflecting on her own hope to consume less of the news and instead pursue the rhetoric to do more to change the world. In Keep the evil out, the artist exposes a private moment of getting cornrows put in. According to Modder, “When I get braids or cornrows it could take a whole day to do, and not once will I step out of the house or salon and risk people seeing half my hair in braids and the other half undone.” She now claims this process and celebrates it in the public eye. Modder's work dares the viewer to see themselves as they wish to be seen, and not as society might depict. She ultimately wants her art to take up space, be accessible and exude truth, hope and joy.

In Lavaughan Jenkins’ newest series, In my feelings, the paintings say the words we did not say to the people we dated or desired to date. His faceless, three-dimensional characters are secretly in conversation with one another, relaying the memories of the artist. In this body of work, Jenkins’ reflects on soulful songs from his childhood, and channels his personal songs of love and pain, literally squeezing them out onto the panels. The series is also inspired by a collaboration between Italian fashion designer, Valentino, and writer/poet, Yrsa Daley-Ward. Daley-Ward wrote a mini, one-line notebook of 25 lines specifically for a clutch designed by Valentino, called Valentino On Love. When considering this collaboration, Jenkins felt the words were written specifically for him — yet also knew they were for everyone. Imagining the people who are in love, and who have fallen out of love, the words inspired both the series and most of the painting titles. In consideration of the many people in the world connected to love, the artwork incorporates new colors throughout the figures, a shift from his typically black depiction of the character’s faces. Jenkins is known for infusing personal emotion into his work, allowing the viewer to interpret the figures using their own experiences and perspectives.

Shona McAndrew’s paintings offer the viewer a glimpse into the spaces and moments where women are truly engaged with themselves on their own terms, not societal ones. After years of depicting herself in her artwork, McAndrew began her Muse series in which the artist invites her friends to participate as the subjects of her paintings. In her most recent painting, Lenny, McAndrew uses Odalisque with Tambourin by Henri Adrien Tanoux as her inspiration imagery. Lenny is a friend of McAndrew’s from her time at Brandeis University. As a trans-woman (pronouns: she/they), Lenny holds high importance to how her identity is shared and shown. McAndrew enjoyed the process of negotiating how to portray the subject, and ensuring that she understood how much power she had in the creation of the painting. McAndrew’s work does just that, it offers a place of courage and confidence — a recognition that one is not alone and the thoughts we have are more commonplace than we realize. The entire series is based on the idea of women as muses and owning their surroundings physically, mentally and emotionally. In Lenny, the window in the background is a progression for this body of work. In McAndrew’s words, “The landscape in the painting is quite vast, of mountains and a lake, and her view feels epic. I like the idea that she’s far up in her little apartment looking out into a world that is all hers.” The idea is romantic yet contains an honesty that the artist consistently portrays in her work. In the inspiration image, Odalisque with Tambourin, the woman’s pose is passive, staring straight ahead at the viewer. She is calm and seems to be waiting for something, for someone to talk to her, to desire her, to want her. In McAndrew’s interpretation of the pose, Lenny is sitting on her bed by a window, with a plate of apples and cheddar, and she is waiting for no one or anything. She just is.

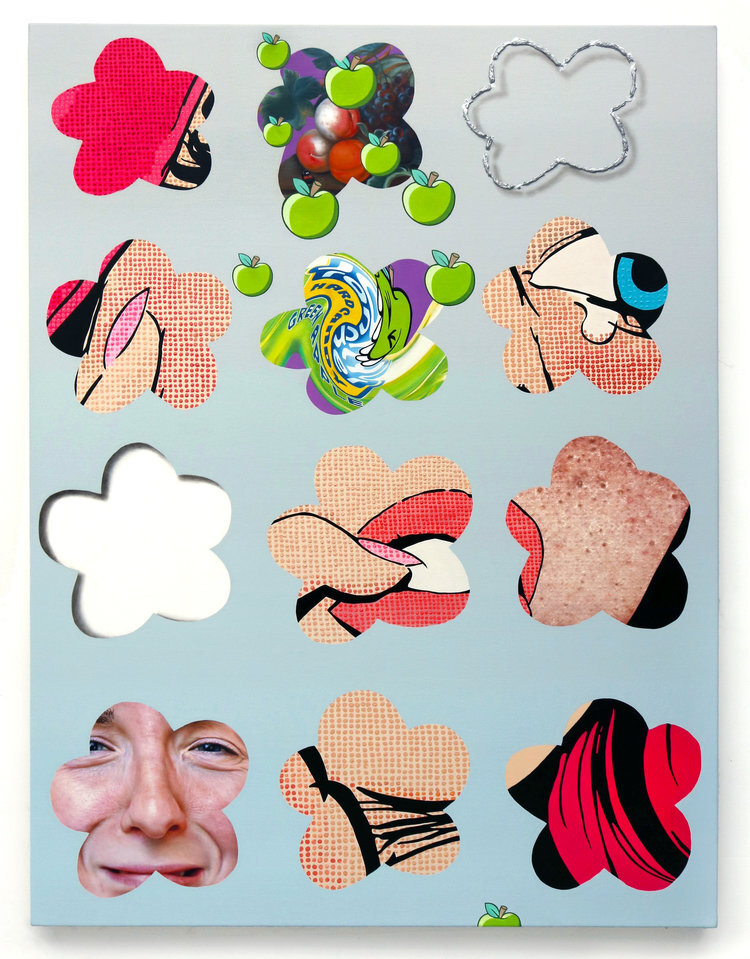

Katelyn Ledford is known for her photorealism paintings containing pop-culture references and self-portraits. Ledford’s artwork is a commentary on how contemporary life is lived partially within digital technologies; thus, we consume masses of images, including ones of people, with no consideration for their context or personhood due to the destruction of image hierarchy. Using shapes, symbols, and images sourced from the internet, she creates de-constructed portraits through various speeds and methods of painting, such as meticulous oil painting, spray paint, and collaged materials. As described by Ledford, “Jolly (Please Don’t Watch Me As I Weep), came through frustration in myself for perceiving other women’s vulnerability as being fake rather than genuine. I wanted to figure out why I would have those judgments to begin with and how I fall into a similar trap.” By juxtaposing a distorted Jolly Rancher ad, a Dutch still-life painting, and a self-portrait in a forced crying face, the artist intentionally contradicts feelings of happiness and sadness. The disparate parts of the painting come together to represent figures of women, and by including herself in the work she simulates emotion and becomes the stereotypes. The tone of the painting lies between sympathy, cynicism, and critique — the viewer unable to differentiate between crying from laughter or pain. Ultimately, Ledford seeks a mode of painting that can slow down the viewer and make them consider our image-saturated, online-obsessed, contemporary reality within the framework of portraiture.

Nathaniel Price’s As Built Drawing series, is about the physicality of the body; the complexity of human anatomy; corporeality and spirituality; morbidity and mortality; illness and health; and art’s transformative qualities. The phrase “as built drawing” refers to architectural drawings documenting the building process and deviations from the original plans that inevitably occur during construction. “As built” in the context of Price’s drawings acknowledges the imperfections, unforeseen conditions, mutations, and transfigurations in the human body and spirit. The series is filled with pathos, but also with light. As Built Drawing began as a systematic framework with a life-size silhouette of a body containing methodical lines of words representing all its organs, muscles, arteries, veins, bones, and nerves, meticulously and accurately placed in their anatomically correct locations. As the series progresses, there is a significant shift as the words migrate outside the perimeter of the body. When this happens, there is a transformation of the content and meaning of the words from anatomically correct terms to the words of illness associated with that region of the body. But at the end, as visualized in As Built Drawing IV, language has transmigrated out of the silhouette, leaving us with pure form—empty, but glowing. Price is a committed working artist, as well as a committed physician and educator. The duality of his professional practices informs these works—not only in their meticulous execution, but also in his empathetic acknowledgement of the inner and outer workings of the human condition.

Using watercolor and ink on paper, Jamie Romanet’s imagery bleeds into itself, creating an introspective space that awakens one’s subconscious and connects Romanet’s subjects to the viewer. Her 8 x 8 inch paintings are a mediation on our humanity and meant to inspire empathy and understanding. The works intentionally express human emotion through facial expressions alone. Romanet believes that our current social dilemma is largely related to how we are growing further and further from one another, becoming isolated, self-concerned, and losing our curiosity and compassion. When placed in a group, the small portraits form the faces of individuals rife with personal difficulties, but also acknowledge the collective benefit of going through the journey together rather than alone.

Woven Profiles is on view at Abigail Ogilvy Gallery in Boston, MA from October 17 — December 1, 2019.